The future is a smart architecture, or digital platform, where each discreet ECU on the vehicle is centralized into three, or perhaps two or even one, computing systems.

Delphi Automotive sees a day very soon when a vehicle’s traditional architecture no longer will be able to handle the computing demands of heightened connectivity and, ultimately, fully autonomous driving, but the supplier thinks it has a solution and wants to be the leading integrator of the technology.

“We have to start thinking of the car as a digital platform,” says Glen De Vos, senior vice president and chief technology officer at Delphi. “And it’s a very different way to think about the car.”

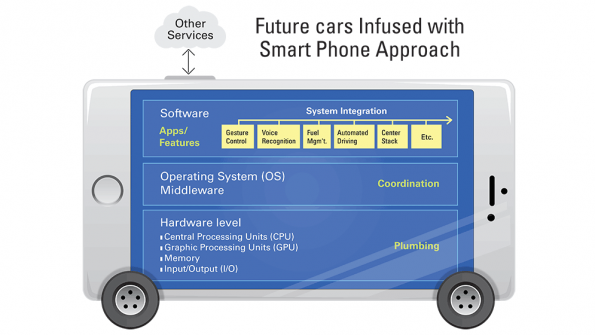

The traditional architecture of a car, which in this case refers to software, wires and electronic control units rather than a common platform of mechanical components underpinning a vehicle, dates back to the 1980s when microprocessors first arrived and were dedicated to individual vehicle functions such as engine management.

Every time a new feature was added, from electric power steering and antilock brakes to DVD screens and emerging advanced driver-assistance systems, each received a dedicated ECU. The controller-area network came along to unite the growing number of ECUs, which is upwards of 100 on some vehicles today, but that architecture is relatively slow and has become increasingly complex to manage.

As a supplier and integrator of those systems, it has been good business for Delphi over the years, De Vos admits. But the traditional architecture soon will be overloaded.

“You just can’t keep adding features,” he says.

The future is a smart architecture, or digital platform, where each discreet ECU on the vehicle is centralized into three, or perhaps two or even one, computing systems. The shift must occur, De Vos says, because the computing demands of future vehicles will be 100 times what they are today. If an automaker’s architecture cannot meet those demands, customers will go elsewhere.

It also will be not just new technologies on the vehicle, but the connectivity owners may bring in from outside, such as the smartphone, or what they may want to download from the cloud. Cybersecurity also will be a greater imperative in the future and it can be managed more effectively from a central computing platform, De Vos offers.

De Vos draws a parallel between the shift to a centralized software-driven vehicle architecture from a fragmented, hardware-based one with the transition to smartphones from cell phones.

“We have to move the car from an appliance to a device,” he says. “The problem has been solved before. The question is how to do it for automotive.”

Moving to a digital platform will not come easily, but automakers will see cost and mass savings through centralization. When Delphi centralized the ADAS features on the Audi A3, De Vos notes, there was a 30% savings in mass and cost.

Tesla is the closest OEM to using a digital platform, evidenced by the electric-vehicle maker’s ability to conduct over-the-air updates to the software in its owners’ cars. But the California startup began with a blank sheet of paper, a luxury established automakers do not enjoy.

“Established automakers have legacies,” De Vos says. “It cannot be done in a single step.”

Audi is the closest of the old-line OEMs, he offers, with its multi-domain controller coming in the next-generation A8 large luxury sedan.

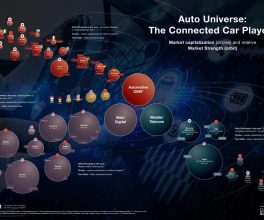

De Vos says it will take more than a decade for the first vehicles with fully digital platforms to arrive and the shift will be incremental, with parts of the smart architecture laid over traditional ones. Delphi recognizes it does not have the knowhow to get the industry to a digital platform independently, so the U.K.-based supplier brought on Silicon Valley automated-driving- and safety-systems startup Renovo as a development partner.

“This is such a sea change,” says Chris Heiser, founder and CEO of Renovo. “It will take many partnerships and consortiums. NASA did not take us to the moon, it was NASA and about 100 other companies.”

Delphi and Renovo see the digital platform first emerging on commercial vehicles, because fleet operators can absorb the initial cost curve more easily with their high utilization rates.

There will not be any moonshot, either, where a traditional automaker develops a one-off architecture for a car using a digital platform. Automakers are far too closely wed operationally to the traditional architecture and, De Vos says, they lack the necessary technical knowledge.

The auto industry moves slowly, too, he adds, due to factors ranging from regulatory requirements to capital-spending limitations.

“There are a lot of reasons to be cautious and conservative,” De Vos says, “but (the digital platform) is inevitable.”

In related news, Delphi announces a commercial partnership agreement with Waterloo, ON, Canada, technology company QNX Blackberry. Blackberry will provide the operating system to Delphi’s autonomous-driving system launching in 2019. Financial details were not released.

Author – James M. Amend

Courtesy of Wards Auto